Ishigaki (石壁) Stone Walls Explained: A Primer in Ishigaki History, Design, and DIY

Traditional Japanese stone walls, or in Japanese “ishigaki” or “ishizumi” are an integral part of Japanese landscaping and garden design. They serve various purposes, including providing structural support, defining boundaries, terracing steep mountains or slopes for farmlands of the inaka (rural Japan), and in old times, defending from castle intruders.

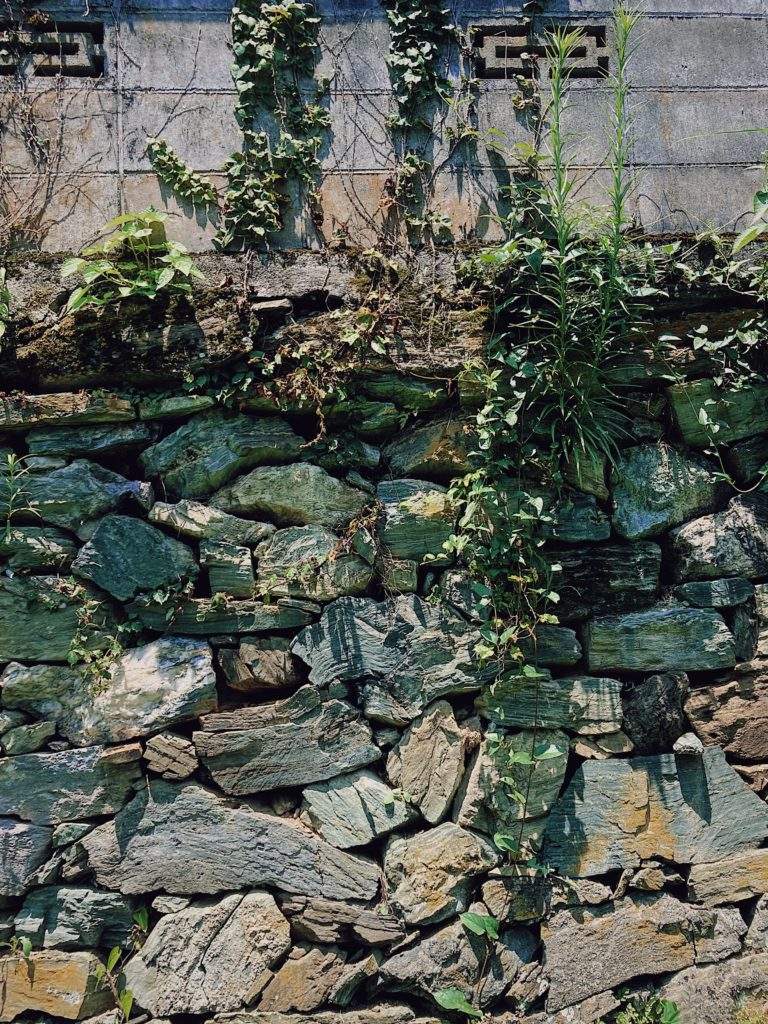

Dry stone wall stacking is a common sight in inaka life, including here in Ehime Prefecture. There are many long-standing (and some not-so-standing) rock walls throughout the mountainous rural landscape.

It allows the slopes to turn the steep mountains into the perfect setting for mikans, kiwi, and rice crops.

But that’s just the surface view of a fascinating traditional trade.

There is something nearly spiritual about taking something from the ground and through the simple act of strategic placement, creating something so natural, strong and beautiful. Stone walls are said to be able to stabilize themselves, rather than try to mechanically suppress the forces of nature.

While stone walls can be seen around the world, the Japanese stone wall was developed elaborately into a specialized trade that differentiates it from other parts of the world. Here are some of the basics on traditional Japanese stone walls.

History

The First Ishigaki Wall in Japan

The use of stone walls in Japan dates back to the Sengoku period. Iimoriyama Castle (飯盛山城) in Osaka Prefecture is thought to be the first known stone wall in Japan, built in 1560. Stones over one meter tall were used to create moats around the main castle building. This castle is now in ruins.

Today, ishigaki stone walls continue to be an essential part of Japan’s architectural heritage and landscape design. Many traditional gardens, temples, and historic sites still feature these stone walls, connecting modern generations to Japan’s rich cultural and historical past. Preservation and restoration efforts are endangered, but remain necessary to ensure that this traditional craftsmanship endures for future generations to appreciate and admire.

A New Life for an Old Technique

Dry stone masonry techniques are a piece of Japanese design heritage to be cherished. They are one of those trades that has proven its brilliance through simplicity, sustainability, and timelessness. Nothing is quite as authentic and charming as a beautifully constructed stone wall.

In addition, the value of a good rock wall extends beyond nostalgia or tradition. A properly built and maintained dry stack rock wall helps to prevent soil runoff during heavy rains, thereby reducing landslide risk.

A Time-Tested Alternative to Concrete

As discussed in the 99% Invisible podcast episode 361, Built on Sand, the rate of construction in the world is so rapid, even sand is becoming an endangered resource due to its use in concrete. And even though concrete is a common sight, it is not so innocent. Guardian called concrete the most destructive material on earth, noting that “if it were a country it would be the world’s worst [C02 emissions] culprit after the US and China.”

This is one more case in which the slow living method wins for environmental consciousness, aesthetics, and performance.

An Endangered Tradition

But as discussed in this interview with a Japanese masonry expert, one of the challenges of creating such a versatile and long-lasting product is the lack of demand. Because once a stone wall is properly constructed and in place, it could stay standing for hundreds of years. And as the techniques can be very labor-intensive, the cost can also be prohibitive when compared to other more “modernized” (concrete) alternatives. Dry masonry techniques are no longer used in public projects. As a result, the market demand is decreased and the trade is endangered.

As we are restoring and maintaining our expansive mountain-side property here in the Japanese countryside, I took a special interest in the stone walls. Mr. Nakamura and I will spend time on the walls, but first, I wanted to spend some time researching stone walls and sharing my findings here in case others could find inspiration, too.

Japanese Stone Work Type Categories

There are three general assembly types for Japanese dry rock masonry. They vary in their processing methods, height abilities, and aesthetics.

Nozura-zumi (野面積)

Nozura-zumi is the most natural way of assembling a stone wall. The stones are not processed/chipped, and they maintain their original shape. The rocks are stacked without concrete or mortar. As the original shape of the rocks will result in gaps and protrusions, there is plenty of room for drainage during heavy rainfall. If the wall is properly constructed using skillful stacking, small stone back-fill and tilt towards the earth, the wall should be fairly resistant to earthquake damage.

Yusumizugaura Terrace Field (遊子水荷浦の段畑) in Uwajima, Ehime.

Potatoes are cultivated on a steep mountain slope averaging 40 degrees.

Uchikomi-hagi (打込接)

Uchikomi-hagi is the next evolution of stone wall construction methods. In this style, the stones are processed, resulting in a flatter face to the stone wall. By chipping the shape of the rocks, a tighter fit is achieved during the stacking process. This results in fewer gaps. Gaps are filled with mazumeishi stones.

Uchikomihagi walls can be seen at Himeji Castle in Hyogo prefecture and Kumamoto Castle in Kyushu.

Kirikomi-hagi (切込接)

Kirikomi-hagi technique uses a higher degree of stone processing, resulting in no gaps. Labor-intensive, this method is restrictively expensive. The lack of drainage necessitates additional rainwater drainage countermeasures. In this method, the stones resemble stacked cubes.

Kirikomi-hagi wall is seen here at Imabari castle in Ehime prefecture.

They can also be seen at Osaka Castle and Nagoya Castle in Aichi Prefecture.

Can I DIY Ishigaki Stone Walls?

You can build your own rock walls, and moving rocks is great strength training. 😉 But improperly constructed rock walls can be a big hazard. A fallen rock wall will be a major waste of time and could cause property damage or personal injury. So be sure to seek guidance or at least refer to a manual (like this one) before investing days in building your own rock wall.

One of the beautiful things about rock walls is that once the fundamental properties are in place, the stacking technique is fairly straightforward. Observing the proper methods for setting a foundation, creating an angle, and back-filling with smaller rocks will result in structural stability.

Building your own rock wall can be a very satisfying project. The building materials can come straight out of the ground so that material costs can be very low.

And from personal experience as I have started to repair and maintain our own rock walls, I can attest to the modest joy of working on a rock wall. There is much happiness hiding in simple tasks, and it is work like this that brings me the most satisfaction in life. I appreciate trades like this that allow me to step lightly on the earth.

Picking up a rock from the earth to create a wall is so simple. But this landscape architecture embodies the wisdom of a centuries-old trade while embodying zero emissions of material transport, manufacturing, processing, etc. What could be more satisfying than that?

Construction Methods

Tools

For the most basic dry stone masonry, only a shovel is needed. For more sophisticated techniques, the following low-tech hand tools are sometimes used:

- chisels

- settou

- geno

- shosen (which are tools for moving stones)

- mokko

Regional Variances

Stacking methods have evolved differently over time between the various regions of Japan. This is due to multiple factors. First is the variety of stone types to be found around Japan – varying in mineral content, shape, size, etc. Second, are the preferences that developed during practice in each area.

Experienced Japanese gardeners and masonry experts can often identify regional influences based on the stacking patterns used in a rock wall.

Integrating Trees and Organic Matter

Organic materials such as pine logs and bundled rice straw have been integrated behind stone walls since ancient times in Japan. Deep-root trees like pine or oak were sometimes planted at the top of masonry walls. Layers of organic matter between back-filled stones allowed for the process of decomposition. The fungal and microbial communities in the soil guide the root system to the face of the stone wall, where the root system sticks to the moist, air-permeable stone wall and cavities.

In these cases, the roots weave between the back-fill rocks and the soil behind them, creating a strong and flexible structural mesh. (source: chiyumori.org)

Ishigaki Workshop

Ishizumi School (一般社団法人石積み学校)

This dry stone wall school is in Ookayama, Tokyo. It is a part of the Tokyo Institute of Technology

Ishigaki Wall Stacking Patterns

Sangizumi (算木積み)

Meaning: counted stacking. In this method, the long and short sides of stones are alternated. The result is a clever interlocking where two or three short sides abut a long edge, and this pattern alternates.

Nunodzumi (布積み)

Meaning: cloth stacking. In this method, a highly uniform and organized face is created.

Tanizumi (谷積み)

Meaning: valley stacking. In this method, the stones fit into their own valley, which creates emphasis on the upward position of the stone’s diagonal axis.

Kikkozumi (亀甲積み)

Meaning: tortoise shell stacking. In this method, the stones are processed into a hexagonal shape. In Gusuku, Okinawa, it is also called Aikatazumi.

Tamaisihzumi (玉石積み)

Meaning: cobblestone. In this method, rounded stones are used. Cobblestones are said to result in less stable construction.

Waraizumi (笑い積み)

Meaning: laughter pile. In this arrangement, small stones around a large stone are said to resemble teeth around an open, laughing mouth.

Recommended Reading

Inside Your Japanese Garden by Joseph Cali and Sadao Yasumoro (English)

誰でもできる石積み入門 Anyone Can Do Japanese Masonry (Japanese language only)

Castle Ishigaki on Touken World (Japanese language only)

Like this article? Pin It!